With Christmas Eve upon us we have all undoubtedly heard the 1984 Classic numerous times. Bob Geldof, Midge Ure and Bono among others have raised millions for impoverished African countries through Band Aid. Raising money and awareness of the issues Africa faces is a worthy challenge and an area in which they have made huge progress. After Michael Buerk's infamous reporting that struck a chord with the nation, Band Aid recorded and produced the song in under 24hrs to help immediately.

The original Band Aid focused particularly on Ethiopia and Eritrea, where in 1984 was one of the worst famines in human history. Food shortages had been ongoing since before 1983 though due to insurgency and poor government policy, as explained by

de Waal. The drought hitting in 1983 is the official reasoning for the famine, however de Waal's analysis shows that famine actually started to occur months before the drought; the problem was just exacerbated by the drought. This is a prime example of a combination of human and physical factors resulting in a large scale problem. The result was 400,000 deaths.

Young goes on to examine how over half of these deaths weren't from famine, they were human rights abuses from counter-insurgency strategies to combat peasant revolutions due to the famine and 'social transformation' in non-insurgency areas.

Recently, the focus has shifted slightly away from East Africa, with Band Aid 30 also focusing on Ebola, a West African crisis.

As someone who has studied African water intensively over the past few months I was shocked by many of the lyrics in the original Band Aid. Some of these lyrics, although aimed at raising money, I believe have severely distorted the average person's view of Africa. Many of the lyrics from Band Aid label Africa as a dark place with no hope, giving the view that everyone is poor and starving. Obviously, this is not the case.

The negative description of Africa begins with:

"There's a world outside your window, And it's a world of dread and fear"

Which is followed by potentially the most damaging line in the song,

"Where the only water flowing is the bitter sting of tears".

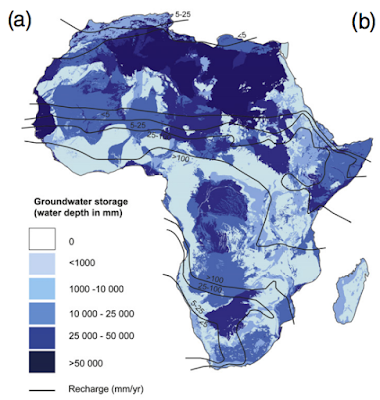

From my research throughout this blog, this is clearly not true. Although originally aimed at Ethiopia, this song is now seen as a symbol for helping all of Africa. Ethiopian rainfall varies significantly throughout the year:

The above graph is approximately 700mm/year. This does vary throughout Ethiopia, with the South generally receiving more than the North. As the North only gets rainfall once a year (due to the Northernmost limit of the ITCZ), it does make it prone to drought if the rains fail. But to have a line in such a popular song hinting there is no water flowing is a generalisation that can morph views.

Having said that, Band Aid 30 has actually cottoned onto this! This lyric has been

removed from the most recent version of the song, replaced with "Where a kiss of love can kill you and there's death in every tear", which I interpreted as an Ebola reference. Although they have removed the original lyric, the replacement is equally depressing. There is one other lyric change from the original: "Well tonight thank God it's them instead of you", is replaced by "Well tonight we're reaching out and touching you". Again, a more PC lyric.

A line not removed, but equally damaging is:

"Oh, where nothing ever grows, no rain or rivers flow"

which is preceded by,

"And there won't be snow in Africa this Christmas time, The greatest gift they'll get this year is life".

Hence, this lyric is clearly aimed at the whole of Africa, not just Ethiopia. To suggest nothing ever grows, there is no rain and no rivers flowing in Africa is absurd.

One of the most famous lines,

"Here's to them, underneath that burning sun"

is another stab at the African climate, suggesting it is the cause of all the problems and the continent is a desert.

|

| What all of Africa looks like (Source) |

Band Aid labels Africa's problems as climate related, but as with the Ethiopian and Eritrean crisis in the 80s, Africa's problems are very much human induced as well. The negative legacy left post-colonially in Africa is extremely well documented in academia and is viewed as often the cause for many disputes which frequently lead to war and disruption/destruction of progress.

Another prominent example, the ever-increasing tensions over the use of the Nile are fuelled by agreements the British Empire made with Egypt (which was a British puppet government at the time,

for in depth case study see here). Egypt still uses such agreements to justify its domination over the other ten countries in the Nile Basin, as Britain granted them permission in 1929 and 1959. The current Nile situation, exacerbated by rising populations and climate change is a tinder-box and a conflict waiting to happen unless action is taken.

As with Ethiopia, these examples are present all over Africa as water shortages, drought and famine occur from human causes just as much as physical. This however, is not represented whatsoever in Band Aid's song. The cause of Africa's problems are climate, and these problems represent the whole of Africa, unfortunately both are so far from the truth.

Many of the water issues in Africa are caused by anthropogenic climate change (changing rainfall patterns and increased temperature) and poor governance. Anthropogenic climate change is clearly not caused by Africa, as discussed earlier in the blog. Poor governance and the role of the West is a huge debate regarding colonial legacies, oil and continued involvement and exploitation.

"Do They Know It's Christmas?" will have had a huge impact on how millions of people view Africa. Some of the stereotypes produced from the lyrics will have influenced in some way any who haven't explicitly studied Africa, which is the vast, vast majority. Given that, the lyrics hit home hard and are exactly what was needed in the Short Term to raise significant amounts of money, as I found out on Channel Five this Christmas Band Aid is the highest selling UK Christmas Number One (selling almost double 2nd place). On the same show Michael Buerk said that although 400,000 had died, without Band Aid that number would be in the millions.

The song has done a lot of good through raising money and awareness, but I feel it has also produced and augmented stereotypes of Africa that have lead to its negative image today.